Behavior Driven Development at Jumia: How it started!

This is not what I asked for!

Verifying that software does what was intended to do in the first place is one of the main challenges in software development. Indeed, several things can go astray while developing software — requirements may be interpreted in different ways by different people, use cases that were not thought of may appear and, as new features are implemented and older ones are changed, it may become difficult to verify that everything keeps working as it should. Furthermore, in modern software development, everything keeps changing very fast, that is, today’s priorities are not the same as tomorrow’s and what’s valuable today may not be valuable tomorrow. If teams are not prepared to cope with fast change, they can easily become overwhelmed, inefficient and, ultimately, frustrated.

Agile software development helps reducing the risk of building the wrong thing (and increases the chances of building the right and most valuable thing first!) by shortening the feedback cycle. Normally this is done by slicing a project into a fixed set of cycles called iterations. These, produce feedback that we can use to steer and adapt the project towards the right direction. However, more often than not, this is implemented disguised as waterfall, for example, teams start by developing a feature and, after the development is done, they test it to make sure they got it right. When a mistake is discovered they have to go back to development, fix the mistake and test the whole thing again. Yes, most of the times these tests are part of a manual regression that can take hours or even days!

TDD (Test Driven Development) speeds-up the feedback loop since tests are written before the implementation and can be used to promptly validate that it is working as expected. This is great! However, these tests are technical-facing, that is, they cannot be understood by most business people. Hence, there is no easy way for them to validate the behavior before the implementation — the risk of mis-implementing requirements is still quite present.

BDD (Behavior Driven Development) is an Agile approach to software development that was originally created to make tests readable by business, i.e., as a mechanism business people could use to verify the expected behavior is implemented. The authors of the fantastic book The BDD Books: Discovery [1] explain that BDD was the missing link between requirements and the software itself: It acts as a bridge, connecting requirements to software. The bridge is made out of concrete examples and represent parts of the required system behavior. The thing about these examples is that both people and machines can understand them, i.e., they are written in plain English but, at the same time, they can be used as automated checks. Each example is a check and is often written using Given When Then keywords. These are called scenarios.

In BDD, the requirements are defined collaboratively by Business and Tech team using the aforementioned examples that can be understood by anyone and reduce the risk of ambiguity and misinterpretations. Furthermore, since these can be used as automated checks, they can continuously verify that the behavior of a system stays the intended one as the it goes through required changes.

In sum, BDD greatly helps delivery teams build the right thing and making sure it continues to behave as intended as the system evolves.

Interesting! How does BDD work then?

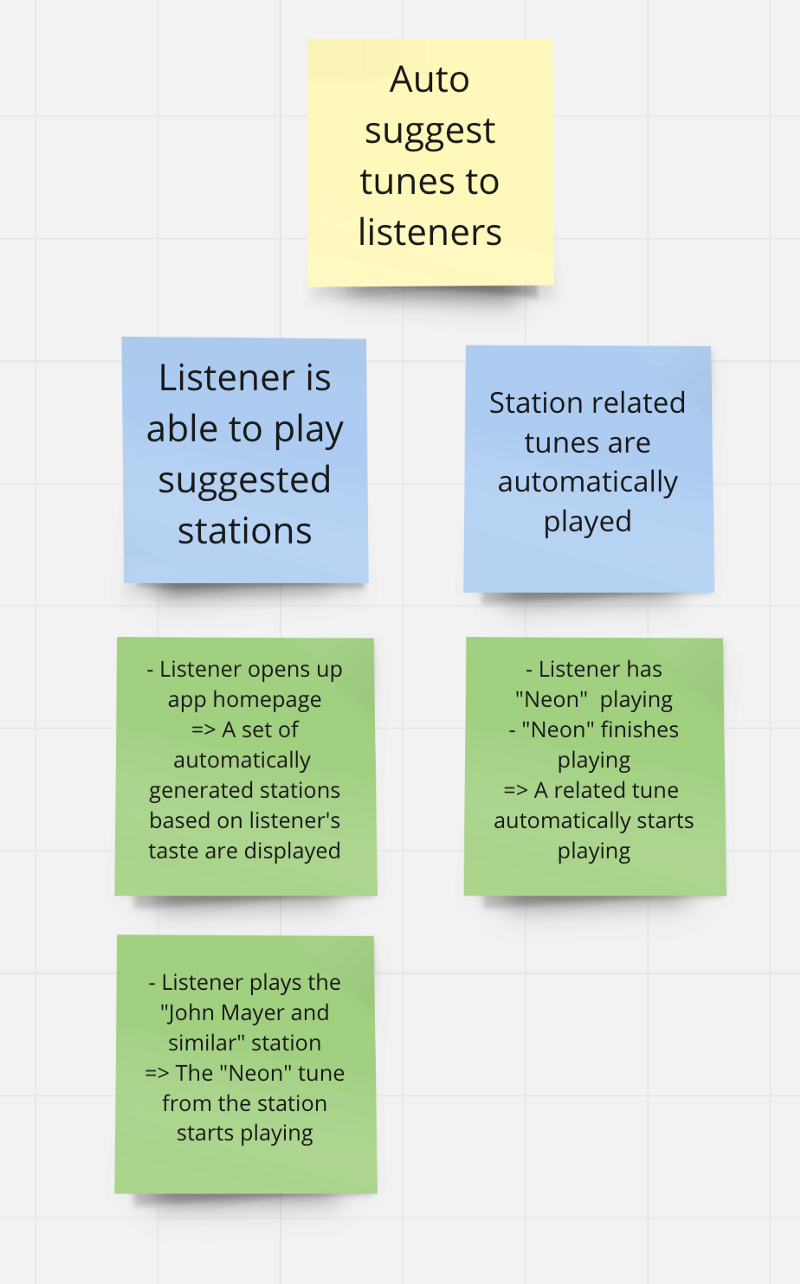

Well, the BDD cycle starts when the delivery team discusses the behavior of a determined user story for the first time. The team gathers and, collaboratively, starts discovering the behavior of a functionality by collecting examples of how the system should work. E.g., let’s say the team needs to implement a feature that automatically suggests tunes for the listener in a music streaming platform. Examples (Green cards) to describe that behavior could look like:

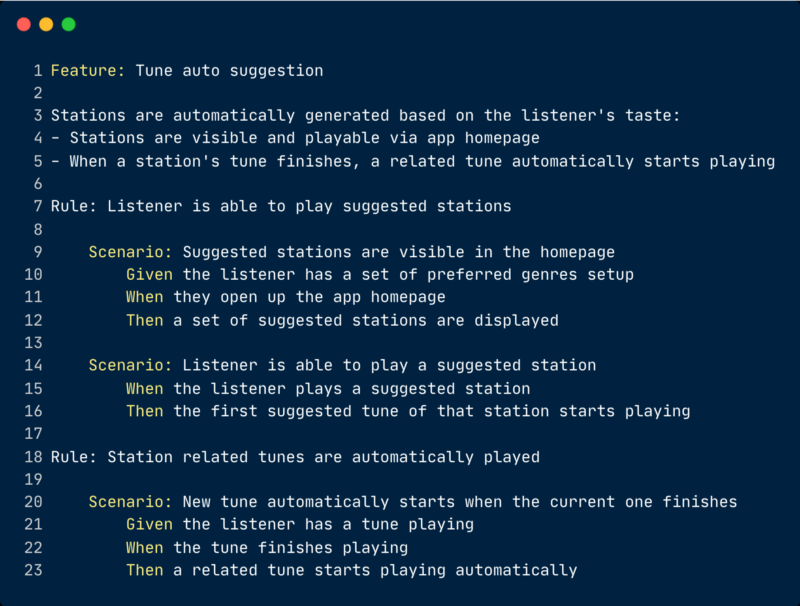

After the examples are collected the team formulates the examples into scenarios. We want these scenarios to drive the development, i.e., the implementation of the behavior. These are executable specification that belong to the application codebase and are used to continuously verify the system behavior. The scenario for the examples above could look like:

The above scenario is written in Gherkin (Given, When, Then keywords) which is one of the most used languages for behavior specifications.

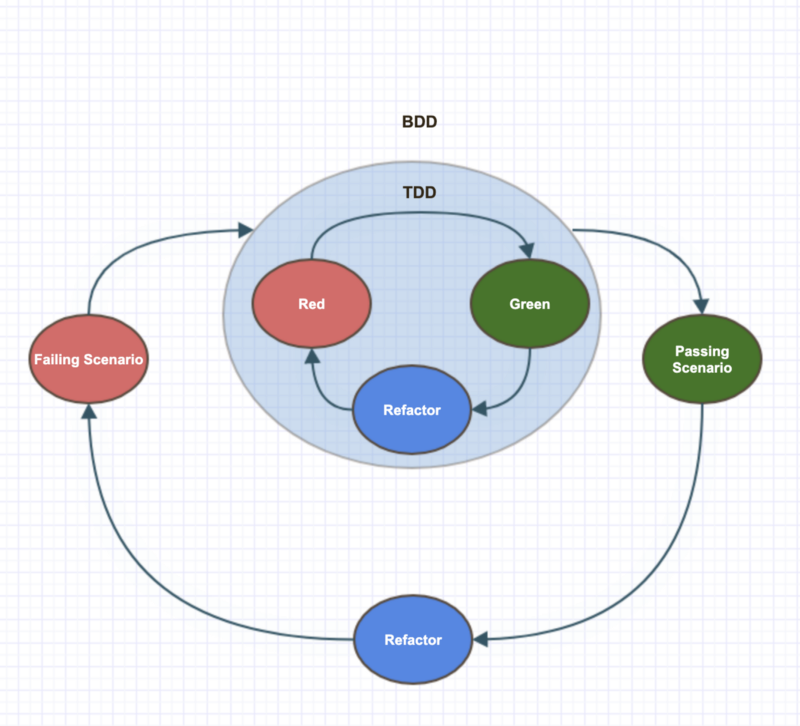

Finally, these scenarios can be implemented as automated checks by the delivery team using a cycle similar to TDD. In TDD, we write a failing test first and then we make it pass by implementing the application code. In BDD, we implement a failing scenario first, representing a portion of behavior, and then we gradually implement the application behavior until the scenario passes. BDD and TDD can work alongside. In fact, the BDD cycle includes the TDD cycle inside as shown by the following picture.

In sum then, BDD is composed by three different practices done in order [1]:

- Discovery: Structured and collaborative activity that uses concrete examples to uncover the ambiguities and misunderstandings that traditionally derail software projects. The goal here is for the team to reach a shared understanding of the behavior to implement.

- Formulation: Process that turns concrete examples produced during discovery into business-readable scenarios. Subsequent review of the scenarios gives confidence that the team really understood what business asked for.

- Automation: Code is written that turns scenarios into tests (automated checks). These give confidence that the application is doing what business intended to do, works as a safety net when code needs to be changed and act as living documentation.

Sounds good! How did you start with BDD anyway?

One of Jumia main businesses is the marketplace platform. This platform has two main clients: the sellers — who sell goods — and the customers — who buys goods. One of the seller facing projects at Jumia is SellerCenter, a platform where sellers can manage their catalog, orders, and finance.

This is a complex and legacy monolith that had already passed through many teams during its lifetime. When our team first started working on it, several problems were faced. For example, the software had a lot of defects requiring intensive support, the documentation was extensive but confusing, and outdated on many points. Most of the times, when we needed to give support to an existing feature, or even implement a new one, there was a lack of business and tech knowledge about what already existed, and we spent a lot of time and effort in investigations, trying to backtrack the business behavior by looking at existing code.

To try to tackle all these problems, we started covering every new development with Acceptance Tests, as well as catching up on the more important already existing features. We were using an internal test framework based on Gherkin that had several pre-built steps for things like payload manipulation, performing requests, asserting responses, and many other useful actions. These were valuable because we were able to effectively reduce the number of defects and develop with more confidence, but they were still too technical facing. Along with the fact that they were “formulated” during the implementation itself, without collaboration from the whole team, they eventually became hard to read and maintain.

Another problem that we would constantly face was: meetings. We followed a structured and organized process based on Scrum, with all the common practices and ceremonies, and most of the times we found ourselves stuck in long meetings, with out-of-scope conversations where communication easily went off-road. We would constantly blame this on the size of the team, which sometimes reached up to almost fifteen people, but slowly we started to realize it was not only that.

To promote continuous learning, one of the common practices some teams use at Jumia, is the book club. Teams choose a book to read and, chapter after chapter, they take notes, share and discuss what they have learned. Typically, this learning is then incorporated in the team process and routine. We came across BDD in one of our book clubs and saw it had a lot of potential to help us overcome the problems we were facing at the time. We started with The BDD Books: Discovery [1] followed by The BDD Books: Formulation [2] and slowly started to incorporate what we learned into the team’s practices and routines. E.g., we rearranged the team routine so that user stories could be discovered using the example mapping technique (a collaborative activity where a user story is explored through concrete examples), and added the formulation step where a subset of the team (three amigos) would formulate the examples discovered by the team into test scenarios. Finally, we also started slowly converting our existing acceptance tests into business-facing ones.

So, what have you observed with these changes?

After a while of implementing BDD practices in our team, these are the main points that we noticed improvement on:

Structured Conversations

We saw a huge improvement in the quality of our meetings. They became much more objective, following a logical progression between the moments when we wanted to discuss a high-level business view as opposed to the moments when we wanted to deep dive into technical details. This was mainly due to the inclusion of the example mapping technique which helped the team focus on the business or behavior details while deferring technical details for later.

Business Facing Tests

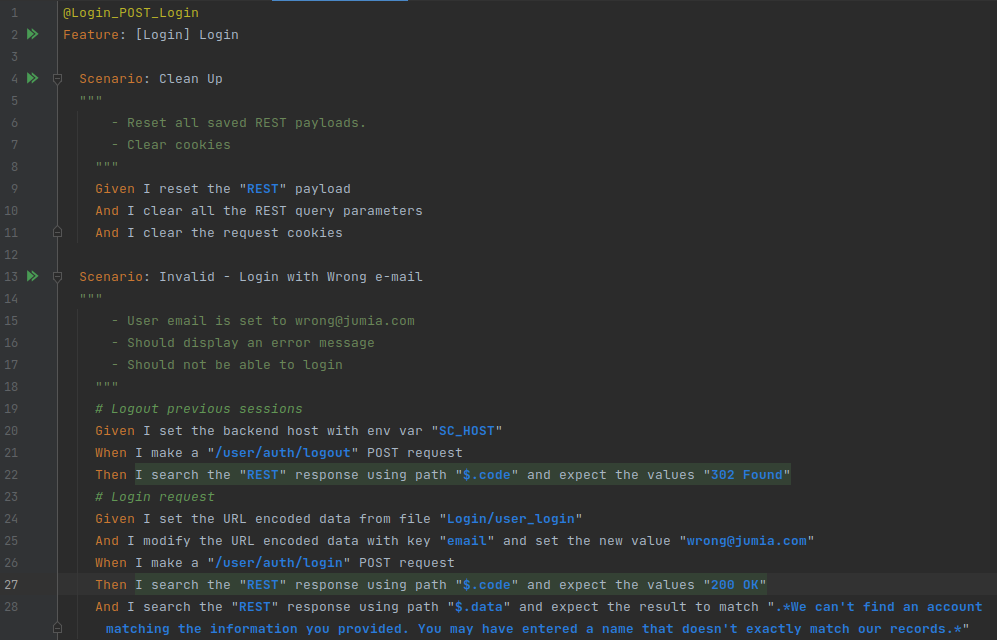

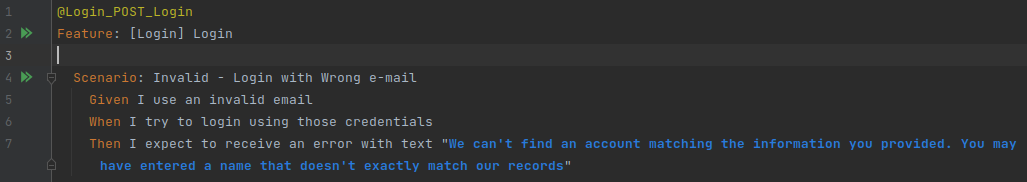

As mentioned, one of the things we started doing was refactoring our acceptance tests in a way that business people could understand them. The following images show the before and after. The team was able to leave behind all the technical terms and think like someone who will be using the application without knowing any technical details in the simplest possible way.

Before:

After:

Although we still didn’t know much about formulation practices (for example using “I” instead of a role or persona), we already saw a huge improvement in readability and in the general understanding of the requirements.

As you can see, the tests are much cleaner, allowing the readers to understand what is the expected behavior of the feature, while all technical details are hidden behind the implementation.

Living Documentation

Traditional documentation usually has some big problems with becoming outdated, complex readability, and not being accessible to non-tech people. By writing feature files in a natural language that describes the requirements of how the application should function, we can have dynamic documentation that not only provides technical knowledge for the engineers but also brings business value to the current system behavior. With the new approach, stakeholders can now review these feature files anytime they want to assert a current feature behavior, which is very useful when giving support or when thinking about new features.

Only implement what is really needed

Another improvement that we were not really expecting to happen was the amount of work that ended up NOT being done. This might seem strange, but with the way that we started slicing the stories and understanding each rule that came with them, we were able to isolate the most important rules and develop them first, while deferring less important rules. They stood in our backlog to be tackled after we finish an MVP, but most of them ended up never being needed again. Taking one feature as an example, 22% of the total user stories were not implemented at all.

Reduced Escaped Defects

Although we already had a low ratio of defects due to the high test coverage with both unit and acceptance tests (tech-oriented), using BDD practices brought even more improvement in that matter. We shifted left QA by involving them in the early stages of discovery and formulation, and we also had the product owner review the scenarios during the formulation stage, guaranteeing that we were implementing the expected behavior. As an example, we saw a whole feature composed of more than 60 user stories with only 1 minor bug reaching production.

Conclusion

BDD is a great way to explore the intended behavior of a feature in a collaborative fashion, greatly reducing the chances of accidental discovery while also ensuring that your software keeps the desired behavior as it evolves. Although full benefits are only achieved if the three BDD practices are adopted, each one gives a set of unique benefits on their own. Hence, if you want to give BDD a try, adopting Discovery is already a good first step.

In the next stories we will zoom in on the first BDD practice: Discovery. Stay tuned!

References

Authors

- Emanuel Fernando Miranda, Director of Engineering Experience at Jumia

- Ravier Meister, Engineering Manager at Jumia